Rhine

| Rhine (Rhein) | |

| River | |

|

|

| Name origin: Proto-Indo-European root *reie- ("to move, flow, run") |

|

| Countries | Switzerland, Italy, Austria, Liechtenstein, Germany, France, Netherlands |

|---|---|

| Rhine Basin | Luxembourg, Belgium |

| Primary source | Vorderrhein |

| - location | Tomasee ("Lai da Tuma"), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland |

| - elevation | 2,345 m (7,694 ft) |

| - coordinates | |

| Secondary source | Hinterrhein |

| - location | Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland |

| - elevation | 2,500 m (8,202 ft) |

| - coordinates | |

| Source confluence | Reichenau |

| - location | Tamins, Graubünden, Switzerland |

| - elevation | 596 m (1,955 ft) |

| - coordinates | |

| Mouth | North Sea |

| - location | Hoek van Holland, Rotterdam, Netherlands |

| - elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| - coordinates | |

| Length | 1,232 km (766 mi) |

| Basin | 170,000 km² (65,637 sq mi) |

| Discharge | |

| - average | 2,000 m3/s (70,629 cu ft/s) |

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| Name | Upper Middle Rhine Valley |

| Year | 2002 (#26) |

| Number | 1066 |

| Region | Europe and North America |

| Criteria | (ii)(iv)(v) |

The Rhine is one of the most important rivers in Europe.

|

|

| Wikimedia Commons: Rhine | |

| [1] | |

The Rhine (Dutch: Rijn; French: Rhin; German: Rhein; Italian: Reno; Latin: Rhenus; Romansh: Rain) is one of the longest and most important rivers in Europe, at about 1,232 km (766 mi),[2][3] with an average discharge of more than 2,000 m3/s (71,000 cu ft/s).

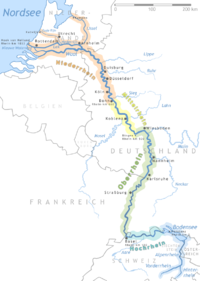

The source of the river is in Switzerland, but at Basel it turns to the north and becomes the frontier between France on the left bank and Germany on the right. At Lauterbourg the frontier turns left while the Rhine continues north through the German Upper Rhineland. Just downstream of Emmerich the river crosses into the Netherlands where it forms a delta, branching into several channels: the principal channel discharges into the North Sea to the west of Dordrecht.

The name of the Rhine derives from Gaulish Renos, and ultimately from the Proto-Indo-European root *reie- ("to move, flow, run"), which is also the root of words like river and run.[4] The Reno River in Italy shares the same etymology. The spelling with -h- seems to be borrowed from the Greek form of the name, Ῥενος (Rhenos),[4] seen also in rheos, stream, and rhein, to flow.

The Rhine and the Danube formed most of the northern inland frontier of the Roman Empire and, since those days, the Rhine has been a vital and navigable waterway carrying trade and goods deep inland. It has also served as a defensive feature and has been the basis for regional and international borders. The many castles and prehistoric fortifications along the Rhine testify to its importance as a waterway. River traffic could be stopped at these locations, usually for the purpose of collecting tolls, by the state that controlled that portion of the river.

The river was an important source of fish, notable for the abundance of its salmon, until the creation of a succession of locks and dams in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries blocked fish access to the middle and upper reaches. Plans exist to install a succession of fish ladders at the locks, and a fish ladder already operates at the Gambsheim lock.

Contents |

Geography

Length

Until 1932 the generally accepted length of the Rhine was 1,230 kilometres (764 miles), but in 1932 the German encyclopedia Knaurs Lexikon stated its length as 1,320 kilometres (820 miles), presumably through a typographical transposition error. This number was then copied the next year in the authoritative Brockhaus Enzyklopädie; apparently no one spotted the mistake, and the new number became generally accepted, finding its way into text books and official publications. Only in 2010 did Bruno Kremer of the University of Cologne notice the discrepancy between the old and then current values; on further investigation he realized that the accepted value of 1320 km was in error. His findings have been checked and confirmed by the Dutch Rijkswaterstaat, who determined the length to be 1,232 kilometres (766 miles).[2][3]

Switzerland, Liechtenstein, Austria, Germany

The Rhine originates at the confluence of the Vorderrhein and Hinterrhein, near Reichenau, Switzerland.

- The Vorderrhein, or Anterior Rhine, springs from Lai da Tuma (Tomasee), near the Oberalp Pass and passes the impressive Ruinaulta or Swiss Grand Canyon.

- The Hinterrhein, or Posterior Rhine, starts from the Paradies Glacier, near the Rheinquellhorn at the southern border of Switzerland. One of its tributaries, the Reno di Lei, is fed by the Lago di Lei reservoir that drains the Valle di Lei in Italy.

From Reichenau, the Rhine flows north as the Alpenrhein, passes Chur, and forms the border between Liechtenstein and then Austria, on the east side and Canton of St. Gallen of Switzerland, on the west side; then empties into Lake Constance. It emerges from Lake Constance, flows generally westward, as the Hochrhein, passes the Rhine Falls, and is joined by the river Aar. The Aar more than doubles the Rhine's water discharge, to an average of nearly 1,000 m3/s (35,000 cu ft/s). The Aar also contains the waters from the 4,274 m (14,022 ft) summit of Finsteraarhorn, the highest point of the Rhine basin. The Rhine roughly forms the boundary with Germany from Lake Constance, until it turns north at the so-called Rhine knee at Basel.

Germany, France

The Rhine is the longest river in Germany. It is here that the Rhine encounters some of its main tributaries, such as the Neckar, the Main and, later, the Moselle, which contributes an average discharge of more than 300 m3/s (11,000 cu ft/s). Northeastern France drains to the Rhine via the Moselle; smaller rivers drain the Vosges and Jura Mountains, uplands. Most of Luxembourg and a very small part of Belgium also drain to the Rhine via the Moselle. It approaches the Dutch border and the Rhine has an annual mean discharge of 2,290 m3/s (81,000 cu ft/s) and an average width of 400 m (1,300 ft).

Between Bingen and Bonn, the Middle Rhine flows through the Rhine Gorge, a formation which was created by erosion, which happened at about the same rate as an uplift in the region, which left the river at about its original level and the surrounding lands raised. This gorge is quite deep and is the stretch of the river which is known for its many castles and vineyards. It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site (2002) and known as "the Romantic Rhine", with more than 40 castles and fortresses from the Middle Ages and many quaint and lovely country villages.

Until the early 1980s, industry was a major source of water pollution. Although many plants and factories can be found along the Rhine up into Switzerland, it is along the Lower Rhine in the Ruhr Area, that the bulk of them are concentrated, as the river passes the major cities of Cologne, Düsseldorf and Duisburg. Duisburg is the home of Europe's largest inland port and functions as a hub to the sea ports of Rotterdam, Antwerp and Amsterdam. The Ruhr, which joins the Rhine in Duisburg, is nowadays a clean river, thanks to a combination of stricter environmental controls, a transition from heavy industry to light industry and cleanup measures, such as the reforestation of slag heaps, spoil tips and brownfields. The Ruhr currently provides the region with drinking water. It contributes 70 m3/s (2,500 cu ft/s) to the Rhine. Other rivers in the Ruhr Area, above all, the Emscher, still carry a considerable degree of pollution.

|

Lai da Tuma (Tomasee) at 2,345 m (7,694 ft). Origin of the Rhine (Anterior) in the canton Graubünden in Switzerland.

|

The Rhine canyon (Ruinaulta) before reaching Chur

|

The Rhine between the upper part (Obersee) and lower part (Untersee) of Lake Constance

|

The Rhine Falls near Schaffhausen

|

|

The Rhine in Basel

|

|

The Rhine between Strasbourg and Kehl

|

A car-ferry across the Rhine at km 372

|

Rhine with chemical industry at Wesseling, near Cologne

|

|

The Rhine in Cologne, Germany

|

Rhine flowing through Düsseldorf, Germany

|

Bridge at Karlsruhe

|

Vorderrhein

|

Rhine near Wageningen

|

Rhine near Mannheim

|

Netherlands

The Rhine turns west and enters the Netherlands, where, together with the rivers Meuse and Scheldt, it forms the extensive Rhine-Meuse-Scheldt delta, one of the larger river deltas in western Europe. Crossing the border into the Netherlands at Spijk, close to Nijmegen and Arnhem, the Rhine is at its widest, although the river then splits into three main distributaries: the Waal River, Nederrijn ("Lower Rhine") and IJssel.

From here, the situation becomes more complicated, as the Dutch name Rijn no longer coincides with the main flow of water. Two-thirds of the Rhine water flows farther west, through the Waal and then, via the Merwede and Nieuwe Merwede (De Biesbosch), merging with the Meuse, through the Hollands Diep and Haringvliet estuaries, into the North Sea. The Beneden Merwede branches off, near Hardinxveld-Giessendam and continues as the Noord, to join the Lek, near the village of Kinderdijk, to form the Nieuwe Maas; then flows past Rotterdam and continues via Het Scheur and the Nieuwe Waterweg, to the North Sea. The Oude Maas branches off, near Dordrecht, farther down rejoining the Nieuwe Maas to form Het Scheur.

The other third portion of the water flows through the Pannerdens Kanaal and redistributes in the IJssel and Nederrijn. The IJssel branch carries one ninth of the water volume north, into the IJsselmeer (a former bay), while the Nederrijn flows west, parallel to the Waal and carries approximately two ninths of the flow. However, at Wijk bij Duurstede, the Nederrijn changes its name and becomes the Lek. It flows farther west, to rejoin the Noord River into the Nieuwe Maas and to the North Sea.

The name Rijn, from here on, is used only for smaller streams farther to the north, which together once formed the main river Rhine in Roman times. Though they retained the name, these streams do not carry water from the Rhine anymore, but are used for draining the surrounding land and polders. From Wijk bij Duurstede, the old north branch of the Rhine is called Kromme Rijn ("Bent Rhine") past Utrecht, first Leidse Rijn ("Rhine of Leiden") and then, Oude Rijn ("Old Rhine"). The latter flows west into a sluice at Katwijk, where its waters can be discharged into the North Sea. This branch once formed the line along which the Limes Germanicus were built. During periods of lower sea levels within the various ice ages, the Rhine took a left turn, creating the Channel River, the course of which now lies below the English Channel.

Larger cities

Basel, Strasbourg, Karlsruhe, Mannheim, Ludwigshafen, Wiesbaden, Mainz, Koblenz, Bonn, Cologne, Düsseldorf, Neuss, Duisburg, Arnhem (Nederrijn), Nijmegen (Waal), Utrecht (Kromme Rijn) and Rotterdam (Nieuwe Maas).

Smaller cities

Chur, Konstanz, Schaffhausen, Breisach, Speyer, Worms, Bingen am Rhein, Rüdesheim am Rhein, Neuwied, Andernach, Bad Honnef, Königswinter, Niederkassel, Wesseling, Dormagen, Zons, Monheim am Rhein, Wesel, Xanten, Emmerich am Rhein, Tiel (Waal), Gorinchem (Boven Merwede), Dordrecht (Oude Maas), Schiedam (Nieuwe Maas), Wageningen (Nederrijn), Rhenen (Nederrijn), Wijk bij Duurstede (Nederrijn), Culemborg (Lek), Vianen (Lek), Schoonhoven (Lek), Gouda (Hollandse IJssel), Leiden (Oude Rijn), Zutphen (IJssel), Deventer (IJssel), Zwolle (IJssel) and Kampen (IJssel).

Railway Crossings

Existing and former railway bridges, with the nearest train stations on the left and right banks:

Vorderrhein

- Switzerland

- A total of five bridges on the line, Andermatt – Reichenau-Tamins (all single tracked, electrified, 1000 mm gauge)

Hinterrhein

- Switzerland

- A total of two bridges on the line, Filisur – Reichenau-Tamins (both single tracked, electrified, 1000 mm gauge)

Alpenrhein

- Switzerland

- At Untervaz (industrial branch line, single tracked and non-electrifed, combined 1005 mm and 1435 mm gauge)

- Between Bad Ragaz and Maienfeld (double tracked, electrified, 1435 mm gauge)

- Liechtenstein and Switzerland

- Between Schaan and Buchs, St. Gallen (single tracked, electrified)

- Austria and Switzerland

- A total of two bridges of the Internationale Rheinregulierungsbahn (both single tracked, electrified, 750 mm gauge)

- Between Lustenau and St. Margrethen (single tracked, electrified)

Hochrhein

- Germany

- Between Konstanz Hbf and Konstanz-Petershausen (single tracked, electrified)

- Switzerland

- Between Etzwillen and Hemishofen (single tracked, non electrified, line closed for traffic)

- Between Feuerthalen and Schaffhausen (single tracked, electrified)

- Between Dachsen and Neuhausen am Rheinfall (single tracked, electrified)

- Between Eglisau and Hüntwangen-Will (single tracked, electrified)

- Switzerland and Germany

- Between Koblenz, Switzerland and Waldshut-Tiengen (single tracked, electrified)

- Switzerland

- Between Basel SBB railway station and Basel Badischer Bahnhof (double tracked, electrified, soon to have four tracks)

Upper Rhine

- France and Germany

- Between Huningue and Weil am Rhein (single tracked, destroyed in WWII)

- Between Chalampé and Neuenburg (single tracked, electrified, freight only — passenger service only on weekends)

- Between Neuf-Brisach and Breisach (single tracked, destroyed in WW2)

- Between Strasbourg and Kehl (single tracked, electrified, soon to be double tracked again)

- Between Rœschwoog and Rastatt-Wintersdorf (double tracked, used as street bridge since 1949, line closed 1960, rails were preserved for strategic purpose until 1999)

- Germany

- Between Karlsruhe-Maxau and Wörth am Rhein-Maximiliansau (double tracked, electrified)

- Between Germersheim and Philippsburg (single tracked, electrified)

- Between Ludwigshafen and Mannheim (four tracks, electrified)

- Between Worms-Brücke and Hofheim (double tracked, electrified)

- Between Mainz-Süd and Mainz-Gustavsburg (double tracked, electrified)

- Between Mainz-Nord and Wiesbaden-Ost (double tracked, electrified)

Middle Rhine

- Germany

- Between Rüdesheim/Geisenheim and Münster-Sarmsheim/Ockenheim (double tracked, destroyed in WW2)

- Between Koblenz Hbf and Niederlahnstein (double tracked, electrified)

- Between Koblenz-Lützel and Neuwied (double tracked, electrified)

- Ludendorff Bridge between Sinzig/Bad Bodendorf and Unkel (double tracked, destroyed in WW2)

Lower Rhine

- Germany

- Two bridges at Cologne:

- The Südbrücke south of the City (double tracked, electrified)

- The Hohenzollernbrücke between Köln Hauptbahnhof and Köln Messe/Deutz railway station (six tracks, electrified)

- Between Neuss-Rheinpark Center and Düsseldorf-Hamm (four tracks, electrified)

- Between Rheinhausen-Ost and Duisburg-Hochfeld Süd (double tracked, electrified)

- Between Moers and Duisburg-Beeck (single tracked (formerly double tracked), electrified, freight only)

- Between Büderich and Wesel (double tracked, destroyed in WWII)

- Two bridges at Cologne:

- Netherlands (in the delta, the river splits and its name changes often)

- Between Nijmegen and Elst, across the Waal River (Rhine delta, main branch) - (double tracked, electrified)

- Between Zaltbommel and Geldermalsen across the Waal River, made famous in a poem by Martinus Nijhoff - (double tracked, electrified)

- At Sliedrecht, across Beneden Merwede - (single track)

- At Rotterdam, across Nieuwe Maas (joint Rhine-Meuse River mouth), former bridge; now replaced by a tunnel (four tracks, electrified).

- At Rotterdam, across Nieuwe Maas-Koningshaven, former bridge 'De Hef' — replaced by a tunnel, disfunct, industrial monument (two tracks, electrified)

- Between Rotterdam and Dordrecht, across Oude Maas, two bridges - (each double tracked, electrified)

- South of Rotterdam, 'HSL' tunnel below Oude Maas - (double tracked, electrified)

- South of Rotterdam, main bridge at Moerdijk across Hollands Diep - (double tracked, electrified)

- South of Rotterdam, 'HSL' second railway bridge - (double tracked, electrified, hi-speed)

- Near Alblasserdam, a tunnel below Noord (a branch near Rotterdam) - (two tracks, electrified; freight only: Rotterdam - Ruhr Area link-up 'Betuwelijn', built 2001-2006).

- Between Bemmel and Zevenaar, tunnel below Pannerdens Kanaal (1707 AD dug section of Rhine's second-largest delta branch) - (two tracks, electrified; freight only: Rotterdam - Ruhr Area link-up 'Betuwelijn', built 2001-2006)

- At Arnhem, across Nederrijn (Rhine delta, second-largest branch) - (two tracks, electrified)

- At Rhenen, across Nederrijn - former double tracked rail bridge, destroyed in WWII.

- Between Culemborg and Houten, across the Lek River (Rhine delta, second-largest branch farther downstream) - (two tracks, electrified)

- At Westervoort, across IJssel - (two tracks, electrified)

- At Zutphen, across IJssel (Rhine, third-largest branch) - (two tracks, electrified)

- At Deventer, across IJssel - (two tracks, electrified)

- At Zwolle, across IJssel, Older bridge - (two tracks, electrified)

- At Zwolle, across IJssel, Second bridge 'Hanzelijn' 2010 - (two tracks, electrified)

- Between Utrecht and Zeist, across Kromme Rijn (east of Bunnik station) - (two tracks, electrified)

- At Utrecht central station, across Vaartsche Rijn (canal) - (four tracks, electrified; building a second bridge with four more tracks is scheduled for 2011-2012)

- At Utrecht central station, across Oude Rijn (canalised into Leidschse Rijn) (fifteen tracks + platforms; electrified).

- Between Utrecht and Vleuten, Woerden, across Amsterdam Rijn-Canal - (four tracks, electrified)

- Between Utrecht and Breukelen, Amsterdam, across Amsterdam Rijn-Canal - (four tracks, electrified)

- At Leiden central station, across Oude Rijn, towards Utrecht (city) - (two tracks, electrified)

- At Leiden, across Oude Rijn, towards Rotterdam - (four tracks, electrified)

The bridges at Huningue, Rastatt, Rüdesheim (Hindenburgbrücke) and Remagen (Ludendorffbrücke), were built for strategic military reasons only, in order to allow the Imperial German Army and later on, the Wehrmacht, to quickly transport forces by rail to Germany's western border in the event of a war with France. Unlike other bridges built for the same purpose, such as the ones at Koblenz or Cologne, these bridges were of almost no use in peacetime and thus, were never rebuilt, after their destruction during the last months of World War II, except for the one at Rastatt, which was used to supply units of the French Army stationed in the area.

Tributaries

Tributaries from source to mouth:

|

Left

|

Right |

Former distributaries

Order: panning North to South through the Western Netherlands:

- Vecht (Utrecht) (minor channel in Roman times, flowing into former Zuider Zee lagoon)

- Kromme Rijn - Oude Rijn (Utrecht and South Holland) (main channel in Roman times, dammed in 12th century AD)

- Hollandse IJssel (formed after Roman times, dammed in 13th century AD)

- Linge (big channel in Roman times, dammed in 14th century AD)

- De Biesbosch-area (initiated by AD 1421–1424 storm surges and river floods, by-passed since the digging of Nieuwe Merwede canal in AD 1904)

The Rhine is navigable for commercial vessels as far as Basel (see Merchant Marine of Switzerland). Between Basel and Rotterdam there are numerous river ports, as well as on the major tributaries, for example Frankfurt am Main.

Navigation on the Rhine is governed by the Central Commission for Navigation on the Rhine. It is responsible for the Rhine from Basel downstream, which counts as international waters.

Canals

The Rhine is also linked to other river systems by canals. List of canals going downstream:

- Rhône–Rhine Canal - Alsace, France.

- Grand Canal d'Alsace — eastern France

- Rhine–Main–Danube Canal — southeastern Germany

- Rhine-Herne Canal — north west Germany, connection to the Dortmund-Ems Canal and the Mittellandkanal

- Wesel-Datteln Canal — north west Germany, connection to the Dortmund-Ems Canal and the Mittellandkanal

- Bijlands Kanaal and Pannerdens Kanaal - eastern Netherlands at German border, dug sections as part of successful 1707 AD attempt to stabilise the Rhine bifurcation into branches Waal and Nederrijn

- Maas-Waal Canal — east central Netherlands

- Amsterdam-Rhine Canal — central Netherlands

- Scheldt-Rhine Canal — south west Netherlands

- Canal of Drusus - Netherlands, Roman historic canal of debated location.

Geologic history

Alpine orogeny

The Rhine flows from the Alps to the North Sea Basin; the geography and geology of its present day watershed has been developing, since the Alpine orogeny began.

In southern Europe, the stage was set in the Triassic Period of the Mesozoic Era, with the opening of the Tethys Ocean, between the Eurasian and African tectonic plates, between about 240 MBP and 220 MBP (million years before present). The present Mediterranean Sea descends from this somewhat larger Tethys sea. At about 180 MBP, in the Jurassic Period, the two plates reversed direction and began to compress the Tethys floor, causing it to be subducted under Eurasia and pushing up the edge of the latter plate in the Alpine Orogeny of the Oligocene and Miocene Periods. Several microplates were caught in the squeeze and rotated or were pushed laterally, generating the individual features of Mediterranean geography: Iberia pushed up the Pyrenees; Italy, the Alps, and Anatolia, moving west, the mountains of Greece and the islands. The compression and orogeny continue today, as shown by the ongoing raising of the mountains a small amount each year and the active volcanoes.

In northern Europe, the North Sea Basin had formed during the Triassic and Jurassic periods and continued to be a sediment receiving basin since. In between the zone of Alpine orogeny and North Sea Basin subsidence, remained highlands resulting from an earlier orogeny (Variscan), such as the Ardennes, Eifel and Vosges.

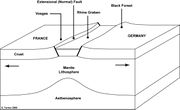

From the Eocene onwards, the ongoing Alpine orogeny caused a N–S rift system to develop in this zone. The main elements of this rift are the Upper Rhine Graben, in southwest Germany and eastern France and the Lower Rhine Embayment, in northwest Germany and the southeastern Netherlands. By the time of the Miocene, a river system had developed in the Upper Rhine Graben, that continued northward and is considered the first Rhine river. At that time, it did not yet carry discharge from the Alps; instead, the watersheds of the Rhone and Danube drained the northern flanks of the Alps.

Stream capture

The watershed of the Rhine reaches into the Alps today, but it did not start out that way.[5] In the Miocene period, the watershed of the Rhine reached south, only to the Eifel and Westerwald hills, about 450 km (280 mi) north of the Alps. The Rhine then had the Sieg as a tributary, but not yet the Moselle River. The northern Alps were then drained by the Danube.

Through stream capture, the Rhine extended its watershed southward. By the Pliocene period, the Rhine had captured streams down to the Vosges Mountains, including the Mosel, the Main and the Neckar. The northern Alps were then drained by the Rhone. By the early Pleistocene period, the Rhine had captured most of its current Alpine watershed from the Rhône, including the Aar. Since that time, the Rhine has added the watershed above Lake Constance (Vorderrhein, Hinterrhein River, Alpenrhein; captured from the Rhône), the upper reaches of the Main, beyond Schweinfurt and the Vosges Mountains, captured from the Meuse River, to its watershed.

Around 2.5 million years ago (ending 11,600 years ago) was the geological period of the Ice Ages. Since approximately 600,000 years ago, six major Ice Ages have occurred, in which sea level dropped 120 m (390 ft) and much of the continental margins became exposed. In the Early Pleistocene, the Rhine followed a course to the northwest, through the present North Sea. During the so-called Anglian glaciation (~450,000 yr BP, marine oxygen isotope stage 12), the northern part of the present North Sea was blocked by the ice and a large lake developed, that overflowed through the English Channel. This caused the Rhine's course to be diverted through the English Channel. Since then, during glacial times, the river mouth was located offshore of Brest, France and rivers, like the Thames and the Seine, became tributaries to the Rhine. During interglacials, when sea level rose to approximately the present level, the Rhine built deltas, in what is now the Netherlands.

The last glacial ran from ~74,000 (BP = Before Present), until the end of the Pleistocene (~11,600 BP). In northwest Europe, it saw two very cold phases, peaking around 70,000 BP and around 29,000–24,000 BP. The last phase slightly predates the global last ice age maximum (Last Glacial Maximum). During this time, the lower Rhine flowed roughly west through the Netherlands and extended to the southwest, through the English Channel and finally, to the Atlantic Ocean. The English Channel, the Irish Channel and most of the North Sea were dry land, mainly because sea level was approximately 120 m (390 ft) lower than today.

Most of the Rhine's current course was not under the ice during the last Ice Age: only the upper reaches of Rhine and Aare in Switzerland were. The Alpine ice cap was one of its sources, but a major part the Rhine discharge under ice age conditions came from annual spring snowmelt. Annual peak discharges and sediment transport capacity in the ice age were higher than in present conditions, causing the active river bed to widen and allowing terraces to develop in the Rhine trunk valley and the valleys of its larger tributaries. A tundra, with Ice Age flora and fauna, stretched across middle Europe, from Asia to the Atlantic Ocean. Such was the case during the Last Glacial Maximum, ca. 22,000–14,000 yr BP, when ice-sheets covered Scandinavia, the Baltics, Scotland and the Alps, but left the space between open tundra and polar desert. Wind-blown dust (loess) and sand (coversand) blew over this landscape and settled in the Rhine Valley and the surrounding hillslopes, contributing to its current agricultural usefulness.

End of the last Ice Age

As northwest Europe slowly began to warm up from 22,000 years ago onward, frozen subsoil and expanded alpine glaciers began to thaw and fall-winter snow covers melted in spring. Much of the discharge was routed to the Rhine and its downstream extension.[6] Rapid warming and changes of vegetation, to open forest, began about 13,000 BP. By 9000 BP, Europe was fully forested. With globally shrinking ice-cover, ocean water levels rose and the English Channel and North Sea re-inundated. Meltwater, adding to the ocean and land subsidence, drowned the former coasts of Europe transgressionally.

About 11,000 years ago, the Rhine estuary was in the Dover Straits. There remained some dry land in the southern North Sea, connecting mainland Europe to Britain. About 9,000 years ago, that last divide was overtopped / dissected. By the time of these events, human habitation had been a feature of the area for some considerable time.

For the last 7,500 years ago, tides and currents have operated very much as they do today. Rates of sea-level rise have dropped so far that natural sedimentation by the Rhine and coastal processes together, could compensate for the transgression by the sea; during the last 7,000 years, the North Sea / English Channel coast line stayed at roughly the same location. In the southern North Sea, due to ongoing tectonic subsidence, the sea-level is still rising, at the rate of about 1–3 cm (0.39–1.2 in) per century (1 metre or 39 inches in last 3000 years).

About 7000–5000 BP, a general warming encouraged migration up the Danube and down the Rhine, by peoples to the east, perhaps encouraged by the sudden massive expansion of the Black Sea, as the Mediterranean Sea burst into it through the Bosporus, about 7500 BP.

Holocene delta

At the begin of the Holocene (~11,700 years ago), the Rhine occupied its Late-Glacial valley. As a meandering river, it reworked its ice-age braidplain. As sea-level continued to rise in the Netherlands, the formation of the Holocene Rhine-Meuse delta began (~8,000 years ago). Coeval absolute sea-level rise and tectonic subsidence have strongly influenced delta evolution. Other factors of importance to the shape of the delta are the local tectonic activities of the Peel Boundary Fault, the substrate and geomorphology, as inherited from the Last Glacial and the coastal-marine dynamics, such as barrier and tidal inlet formations.[7]

Since ~3000 yr BP (= years Before Present), human impact is seen in the delta. As a result of increasing land clearance (Bronze Age agriculture), in the upland areas (central Germany), the sediment load of the Rhine River has strongly increased[8] and delta growth has sped up.[9] This caused increased flooding and sedimentation, ending peat formation in the delta. The shifting of river channels to new locations, on the floodplain (termed avulsion), was the main process distributing sediment across the subrecent delta. Over the past 6000 years, approximately 80 avulsions have occurred.[5] Direct human impact in the delta started with peat mining, for salt and fuel, from Roman times onward. This was followed by embankment, of the major distributaries and damming of minor distributaries, which took place in the 11–13th century AD. Thereafter, canals were dug, bends were short cut and groynes were built, to prevent the river's channels from migrating or silting up.

At present, the branches Waal and Nederrijn-Lek discharge to the North Sea, through the former Meuse estuary, near Rotterdam. The river IJssel branch flows to the north and enters the IJsselmeer, formerly the Zuider Zee brackish lagoon; however, since 1932, a freshwater lake. The discharge of the Rhine is divided among three branches: the River Waal (6/9 of total discharge), the River Nederrijn - Lek (2/9 of total discharge) and the River IJssel (1/9 of total discharge). This discharge distribution has been maintained since 1709, by river engineering works, including the digging of the Pannerdens canal and since the 20th century, with the help of weirs in the Nederrijn river.

Prehistory

Paleolithic

During the Middle Paleolithic (ca 100,000–30,000 BP), Western Europe, including the Rhine and Danube Valleys, was occupied by the Neanderthal, to which belonged the Mousterian culture of stone tools. Mousterian sites are not considered intrusive. It is believed that the Neanderthals may have evolved from the preceding Homo erectus in the vicinity of the glaciers, but the question has by no means been settled definitively.

Neanderthal sites are denser to the south, where open forest prevailed and the limestone terrain offered more caves as dwellings. The Rhine ran through an open tundra, where Neanderthals hunted big game, such as the rhinoceros and the woolly mammoth. Accordingly, open air Mousterian sites have been discovered in and around the Rhine valley.

Mesolithic

Before approximately 5600 BC, the Rhine Valley, along with most of Europe, was occupied by Cro-Magnon man, in the Mesolithic stage of cultural development; that is, they hunted and gathered, but owned a larger and more specialized tool kit than the Paleolithic people, knew more about the plants and animals, and even may have kept a few animals.

Iron Age

During the early Iron Age, both banks of the Rhine were inhabited by Celtic tribes. However, in the beginning of the Pre-Roman Iron Age (ca 600 BC), the Proto-Germanic tribes crossed the Weser River and the Aller, expanding the whole distance to the banks of the Rhine. This expansion is shown archaeologically in the form of the Jastorf culture. From ca 500 BC onwards, the lower Rhine, not the Weser or the Aller, would increasingly mark the border between the Celtic and Germanic tribes.

Historic and military relevance

The human history of the Rhine begins with the writers of the late Roman Republic and early Roman Empire. Nearly all the classical sources mention the Rhine and the name is always the same: Rhenus in Latin or Rheonis in Greek. The Romans viewed the Rhine as the outermost border of civilization and reason, beyond which were mythical creatures and wild Germanic tribesmen, not far themselves from being beasts of the wilderness they inhabited.

As it was a wilderness, the Romans were eager to explore it. This view is typified by Res Gestae Divi Augusti, a long public inscription of Augustus, in which he boasts of his exploits; including, sending an expeditionary fleet north of the Rheinmouth, to Old Saxony and Jutland, which he claims no Roman had ever done.

Throughout the long history of Rome, the Rhine was considered the border between Gaul or the Celts and the Germanic peoples; although, it should be noted that the historical ethnonyms do not carry their modern ethno-linguistic definitions. Typical of this point of view is a quote from Maurus Servius Honoratus, Commentary on the Aeneid of Vergil (On Book 8 Line 727):

- "(Rhenus) fluvius Galliae, qui Germanos a Gallia dividit"

- "(The Rhein is a) river of Gaul, which divides the Germanic people from Gaul."

The Rhine, in the earlier sources, was always a Gallic river.

As the Roman Empire grew, the Romans found it necessary to station troops along the Rhine. They kept two army groups there (exercitus), the inferior or "lower", and the superior or "upper", which is the first distinction between upper Germania and lower Germania. It originally probably only meant upstream and downstream ("Niederrhein" and "Oberrhein", respectively; see the map above).

The Romans kept eight legions in five bases along the Rhine. The actual number of legions present at any base or in all, depended on whether a state or threat of war existed. Between about AD 14 and 180, the assignment of legions was as follows: for the army of Germania Inferior, two legions at Vetera (Xanten), I Germanica and XX Valeria (Pannonian troops); two legions at oppidum Ubiorum ("town of the Ubii"), which was renamed to Colonia Agrippina, descending to Cologne, V Alaudae, a Celtic legion recruited from Gallia Narbonensis and XXI, possibly a Galatian legion from the other side of the empire.

For the army of Germania Superior: one legion, II Augusta, at Argentoratum (Strasbourg); and one, XIII Gemina, at Vindonissa (Windisch). Vespasian had commanded II Augusta, before his promotion to imperator. In addition, were a double legion, XIV and XVI, at Moguntiacum (Mainz).

The two originally military districts, of Germania Inferior and Germania Superior, came to influence the surrounding tribes, who later respected the distinction in their alliances and confederations. For example, the upper Germanic peoples combined into the Alemanni. For a time, the Rhine ceased to be a border, when the Franks crossed the river and occupied Roman-dominated Celtic Gaul, as far as Paris.

The first urban settlement, on the grounds of what is today the centre of Cologne, along the Rhine, was Oppidum Ubiorum, which was founded in 38 BC, by the Ubii, a Germanic tribe. Cologne became acknowledged, as a city by the Romans in AD 50, by the name of Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium. Considerable Roman remains can be found in contemporary Cologne, especially near the wharf area, along the Rhine, where a notable discovery, of a 1900 year old Roman boat, was made on the Rhine banks, in late 2007.[10]

Subsequently, language changes began to play a major political role. West Germanic dissimilated into Low Saxon; Low Franconian languages and High German languages, roughly along the old lines. Perhaps, it had been doing so all along. Charlemagne united all the Franks in the Holy Roman Empire, but he did not rule over a people of uniform language. After his death, the empire split, more or less along language lines, with the Low Franconian being spoken in the Netherlands and the Low Saxon and High German, in what became Germany. The Romanized Franks became the French. The Rhine once again became a political border.

The Rhine as a border has been and still is a mystical and political symbol. German authors and composers have written reams about it. During World War II, it was still considered the sacred border, of Germany and still was a defensive barrier.

Historical context

The Rhine is closely linked to many important historical events — particularly military ones — as well as myths. For example:

- The Battle of the Teutoburg Forest, which finally established the Rhine as the northern frontier of the Roman Empire.

- It was a historic object of frontier trouble, between France and Germany. Establishing "natural borders" on the Rhine was a long term goal of French foreign policy, since the Middle Ages; though, the language border was — and is — far more to the west. French leaders, such as Louis XIV and Napoleon Bonaparte, tried with varying degrees of success to annex lands west of the Rhine. The Confederation of the Rhine was established by Napoleon, as a French client republic, in 1806 and lasted until 1814, during which time it served as a significant source of resources and military manpower for the First French Empire. In 1840, the Rhine crisis evolved, because the French prime minister, Adolphe Thiers, started to talk about the Rhine border. In response, the poem and song, Die Wacht am Rhein (The Watch on the Rhine), was composed at that time, calling for the defense of the western bank of the Rhine against France. During the Franco-Prussian War, it rose to the de-facto status of a national anthem in Germany. The song remained popular in World War I and was used in the movie Casablanca.

- At the end of World War I, the Rhineland was subject to the Treaty of Versailles. This decreed that it would be occupied by the allies until 1935 and after that, it would be a demilitarised zone, with the German army forbidden to enter. The Treaty of Versailles and this particular provision, in general, caused much resentment in Germany and is often cited as helping Adolf Hitler's rise to power. The allies left the Rheinland in 1930 and the German army re-occupied it in 1936, which was enormously popular in Germany. Although the allies could probably have prevented the re-occupation, Britain and France were not inclined to do so, a feature of their policy of appeasement to Hitler.

- In World War II, it was recognised that the Rhine would present a formidable natural obstacle to the invasion of Germany, by the western allies. The Rhine bridge at Arnhem, immortalized in the book, A Bridge Too Far and the film, was a central focus of the battle for Arnhem, during the failed Operation Market Garden of September 1944. The bridges at Nijmegen, over the Waal distributary of the Rhine, were also an objective of Operation Market Garden. In a separate operation, the Ludendorff Bridge, crossing the Rhine at Remagen, became famous, when U.S. forces were able to capture it intact — much to their own surprise — after the Germans failed to demolish it. This also became the subject of a film, The Bridge at Remagen.

- On March 27, 1977, the Tenerife disaster occurred in Tenerife in the Canary Islands. One of the aircraft involved, KLM Flight 4805, was a 747 registered as "The Rijn (Rhine)."

- In November 1986, fire broke out in a chemical factory near Basel, Switzerland. Chemicals soon made their way into the river and caused pollution problems. About 30 tons of chemicals were discharged into the river. Locals were told to stay indoors, as foul smells were present in the area. The pollutants included pesticides, mercury, and other highly poisonous agricultural chemicals.

- Mainz Cathedral — this more than 1,000-year-old cathedral is seat to the Bishop of Mainz. It holds significant historic value, as the seat of the once politically powerful secular prince-archbishop within the Holy Roman Empire. It houses historical funerary monuments and religious artifacts.

- The Nibelungenlied, an epic poem in Middle High German, tells the saga of Siegfried/Sigurd, who killed a dragon on the Drachenfels (Siebengebirge) ("dragons rock"), near Bonn at the Rhine and of the Burgundians and their court at Worms, at the Rhine and Kriemhild's golden treasure, which was thrown into the Rhine by Hagen.

- Das Rheingold — inspired by the Nibelungenlied, the Rhine is one of the settings for the first opera of Richard Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen. The action of the epic opens and ends underneath the Rhine, where three Rheinmaidens swim and protect a hoard of gold.

- The Loreley/Lorelei is a rock on the eastern bank of the Rhine, that is associated with several legendary tales, poems and songs. The river spot has a reputation for being a challenge for inexperienced navigators.

- Many historic castles are located along the Rhine.

- Seven Days to the River Rhine was a Warsaw Pact war plan for an invasion of Western Europe during the Cold War.

See also

- KD Steamer

- Witenwasserenstock (triple watershed: Rhone–Rhine–Po)

- Piz Lunghin (triple watershed: Po–Rhine–Danube)

- Sandoz chemical spill

Notes

- ↑ Frijters and Leentvaar (2003)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Schrader, Christopher; Uhlmann, Berit (March 28, 2010). "Der Rhein ist kürzer als gedacht – Jahrhundert-Irrtum" (in German). sueddeutsche.de. http://www.sueddeutsche.de/wissen/981/507145/text/. Retrieved 2010-03-27.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Rhine River 90km shorter than everyone thinks". The Local – Germany's news in English. March 27, 2010. http://www.thelocal.de/society/20100327-26161.html. Retrieved 2010-04-09.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Rhine". Online Etymology Dictionary. Douglas Harper. November 2001. http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=Rhine. Retrieved 2009-02-10.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Berendsen and Stouthamer (2001)

- ↑ Ménot et al. (2006)

- ↑ Cohen et al. (2002)

- ↑ Hoffmann et al. (2007)

- ↑ Gouw and Erkens (2007)

- ↑ DPA (9 December 2007). "Roman barge under Cologne to reveal shipping history - Feature". The Earth Times. http://www.earthtimes.org/articles/show/155522.html. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

References

- Berndsen, Henk J.A.; Stouthamer, Esther (2001). Palaeogeographic Development of the Rhine-Meuse Delta, The Netherlands. Assen: Koninklijke Van Gorcum. ISBN 9023236955. OCLC 495447524. http://www.geo.uu.nl/fg/palaeogeography/books/palaeogeographic-development.

- Blackbourn, David (2006). The Conquest of Nature: Water, Landscape, and the Making of Modern Germany. London: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 0224060716. OCLC 224244112.

- Cohen, K.M.; Stouthamer, E.; Berendsen, H.J.A. (February 2002). "Fluvial Deposits As a Record for Late Quaternary Neotectonic Activity in the Rhine-Meuse Delta, The Netherlands". Netherlands Journal of Geosciences – Geologie en Mijnbouw 81 (3-4): 389-405. ISSN 0016-7746. http://www.njgonline.nl/publish/articles/000210/article.pdf.

- Frijters, Ine D.; Leentvaar, Jan (2003). Rhine Case Study. Technical documents in hydrology, no. 17. Paris: UNESCO International Hydrological Programme, (Rep. No. SC/2003/WS/54). OCLC 55974122. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0013/001333/133303e.pdf.

- Gouw, M.J.P.; Erkens, G. (March 2007). "Architecture of the Holocene Rhine-Meuse delta (the Netherlands) – A result of changing external controls". Netherlands Journal of Geosciences – Geologie en Mijnbouw 86 (1): 23-54. ISSN 0016-7746. http://www.njgonline.nl/publish/articles/000306/english.html.

- Hoffmann, T.; Erkens, G.; Cohen, K.; Houben, P.; Seidel, J.; Dikau, R. (2007). "Holocene Floodplain Sediment Storage and Hillslope Erosion Within the Rhine Catchment". The Holocene 17 (1): 105-118. doi:10.1177/0959683607073287.

- Ménot, Guillemette; Bard, Edouard; Rostek, Frauke; Weijers, Johan W.H.; Hopmans, Ellen C.; Schouten, Stefan; Sinninghe Damsté, Jaap S. (15 September 2006). "Early Reactivation of European Rivers During the Last Deglaciation". Science 313 (5793): 1623-1625. doi:10.1126/science.1130511.

- "Rhine River History". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2010. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/501316/Rhine-River/34453/History. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- Roll, Mitch (2009). "Rhine River History and Maps". The ROLL "FAME" Family. http://www.rollintl.com/roll/rhine.htm. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

External links

|

||||||||||